What Business Can Learn From Social Movements

Chicago, Illinois is the place I call home. The Windy City is recognized for its hardball politics and organizing history. In the late 1800s, the Pullman Strike led to major advances in improved labor law. Saul Alinsky, a well known community activist, spent his career in Chicago. He authored Rules for Radicals, still a popular handbook for organizers. His work with Chicago Industrial Area Foundation in the Back of Yards neighborhood catapulted him into organizing notoriety. Alinsky later helped found The Woodlawn Organization, a key player in the 1960s Chicago civil rights movement. The city’s rich history of activism laid the foundation for my own brief moment in organizing.

Right out of college, I was idealistic. I still am. But in my early twenties I had less financial obligation to hinder my aspirations of changing the world than I do now. When I attended my first and last job fair, the role that most interested me was a six month internship in community organizing. I spent an hour at my future mentor’s assigned table talking with him about social change as he convinced me that mobilizing every day people was the best method for systemic progress. Instead of accepting a full time job when I finished my final college course, I signed up for the internship.

I was assigned a campaign centered around police brutality on Chicago’s south side. I spent my days meeting with residents, community leaders, and local politicians in order to build a power analysis of a specific neighborhood. By the time I finished my commitment, I was fully convinced in the potential of organizing regular people to effect change for themselves. Even though I searched for a paid role in organizing after my internship ended, I did not find one. Instead, my need to pay the bills won at that moment in my life. The job that I found next was in corporate America.

Today I believe that for-profit social enterprise can also be a vehicle for the type of change we want to see in the world. But we do need good policy to support systems that provide quality of life for all. While social media has changed the dynamics and expanded the parameters of organizing, change in society occurs because every day people choose to be vocal about what matters.

I found my way back to social impact work fairly quickly because I was more interested in solving people problems than I was in selling equipment and parts. Over the course of my tenure in business, I grew into senior leadership roles and then executive roles. But community organizing lessons stuck with me. I learned some of my best leadership lessons during my days walking the streets of the inner city, trying to build a power analysis of local community organizations.

Be clear. Clarity in your work is absolutely essential. In community organizing, you need to know your ask before you approach a political leader or decision maker. Sometimes you only get one opportunity to present your request. Before you can take any action, you need to get specific on the problem and what you want from the other party. It is difficult to get someone else to say yes when they do not understand how to solve your concern. Reflection, community listening, goal setting, and planning are necessary to get to a clear request. Solving a complex community problem requires deep thinking and deep listening. Sometimes in business (and life) we want to skip these steps because they appear time consuming.

A leader is a leader because they have direction. It is difficult to convince someone to genuinely follow your leadership when they do not believe you are clear on where you are going. As a leader, when you are not clear on your own objectives you will always fail to communicate clearly. Poor communication creates unnecessary conflict and fuzzy expectations. Unclear expectations harm morale. Without clear objectives, decision makers also fall prey to chasing shiny objects or whatever initiative the competition seems to be executing successfully. Vision and mission comes from clarity of purpose. Those are business differentiators.

People know how to solve their own problems. Community organizing is largely based around a framework called asset-based community development. It is rooted in the recognition that marginalized communities understand the issues they face and have tremendous internal and social resources to identify solutions. Once these resources are mobilized and coordinated, communities can achieve tremendous outcomes. The results are usually much more impactful than solutions produced by outsiders.

In business environments, the lowest paid employees are often the most overlooked. Their perspective is not often tapped into for business strategy. If you overlook your frontline team, you ignore a valuable source of business information. Those who interact with your customers regularly know your company’s pain points and weaknesses. Because they have to address the problem, they likely have a good sense of how it needs to be resolved. When respect is hierarchically related to position and title, critical insight goes missing. Listen to your frontline team and find ways to develop them into roles with greater responsibility.

Develop people into leadership by understanding their motivations. Old fashioned organizing involves understanding the self-interests of those you recruit to your cause. If you have ever had coffee with an organizer, they likely got you to share stories about yourself that you never intended to share. They are trained in understanding motivations. When people see the connection between your cause and their personal cause (or self-interest) they are more likely to genuinely engage.

Leaders understand what motivates those they are leading. Businesses often operate with a partial understanding of various motivations. A human resources department may pull together a variety of incentive plans that are designed to address different individual motivations. These could include an array of options — items like bonus compensation structures, ongoing training and education, opportunities for external visibility, flexible scheduling and more end up on the list. Then many businesses and managers leave it up to the employee to figure out how to motivate themselves by choosing the right reward.

Leaders develop people by understanding motivations of the specific individuals on their team rather than just offering aggregate options. Teams do not create remarkable results when people are unmotivated. When you inspire and develop your team to achieve outcomes that are also meaningful to them personally, the resulting performance can be powerful. The collective capacity of a fully engaged team goes very far.

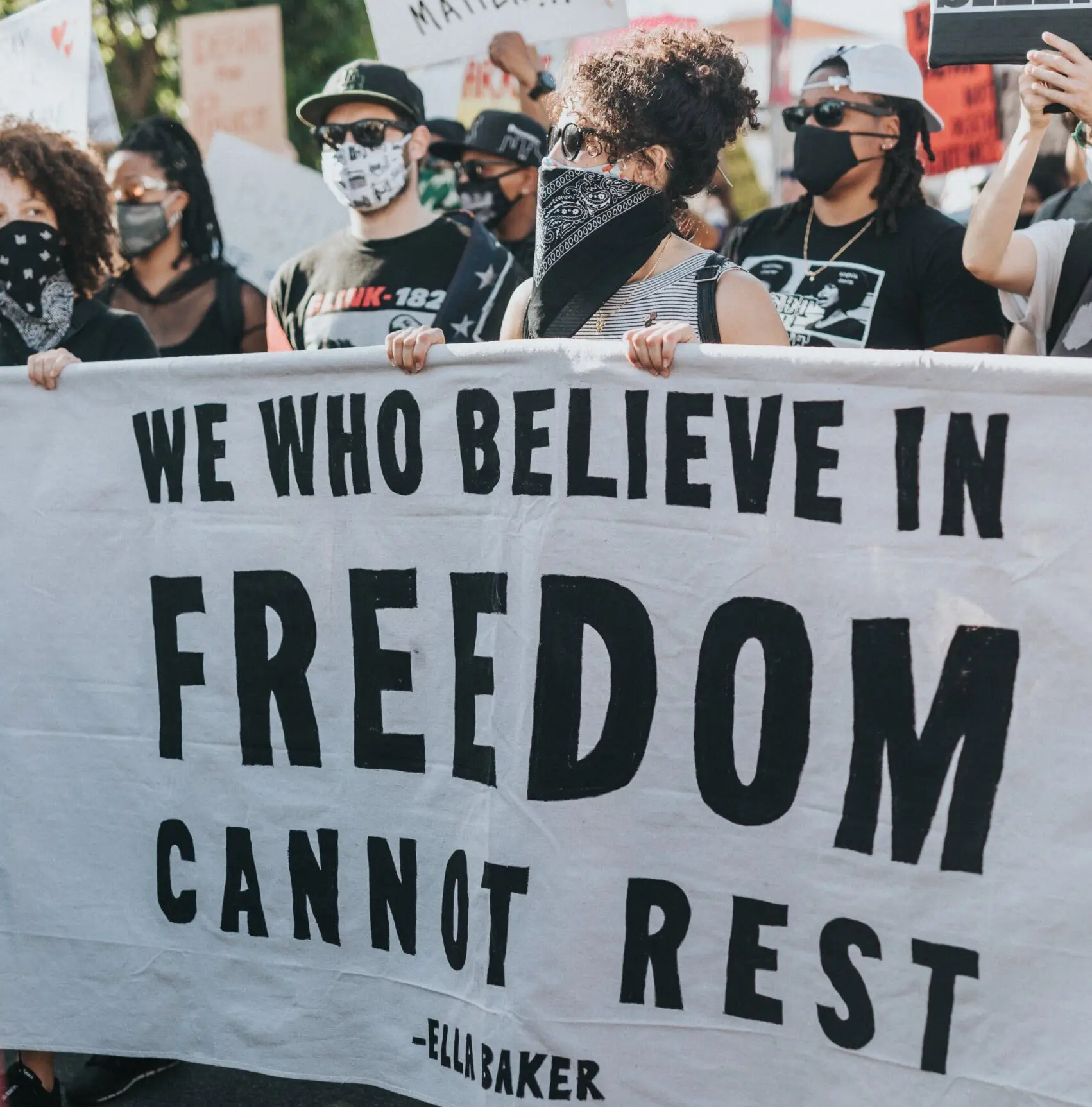

Social movements are relevant. Broadly, they speak to innate desires like safety, justice, access to resources, and other human rights issues. Movements empower people who are often overlooked, and allow people to feel like their voices matters. They often arise because of an injustice, so they are rooted in a sense of justice and equity. Successful movements are based on a sense of purpose greater than the individual self. Even when a movement does not produce immediate policy results, the momentum begins to change the local or national conversation.

Businesses have the opportunity to do the same, if we as leaders are willing to take lessons from those in our community who are making their voices heard in the streets instead of solely listening to those in the board rooms.

THIS ARTICLE FIRST APPEARED ON MEDIUM.